Holy Week in Zamora, Spain

It's about tradition & reflection; no religious affiliation is required

When I was 15, my parents visited Spain over Easter and experienced Seville’s Semana Santa, or Holy Week. I was fascinated when they showed me the pics (there was no Instagram back then, we had to wait for the film to be developed). The pictures raised all sorts of questions - how was it that an entire week was dedicated to processions? Were people off school and work? Why did the participants look like Ku Klux Klan members?

And why wouldn’t my parents stop talking about Semana Santa?

(When I say they didn’t stop talking about it, I mean… they talked about the experience for years.)

NOTE TO FUTURE SELF: INVESTIGATE SEMANA SANTA

So, onto my bucket list, Semana Santa went. Since my parents experienced it in Seville… I naturally associated Holy Week in Spain with Seville. I never considered it to be celebrated throughout the country. (And hello, I majored in Spanish and taught it as well… yet, in my mind, there was one Holy Week in Spain.)

I learned how wrong I was while volunteering at a language immersion in La Alberca, Spain. One of the participants was Isabel - a gal from Zamora, a Spanish city I’d never heard of. Isabel told me all about her city- its history, impressive collection of Romansque art, churches, river… the whole nine yards.

My ears perked up, of course, when Isabel talked about Zamora’s famous wine & cheese, and then, even more, when she mentioned the celebration that puts it on the map - Semana Santa.

Memories of my parents’ trip popped into my head, as did my vow to experience it one day.

Isabel explained that Zamora’s Semana Santa is different from others found throughout Spain - it’s one of Spain’s oldest celebrations and is a more solemn, reflective experience than the others. I learned that the “pasos” (floats with religious figures) are much simpler than other Semana Santa pasos and feature authentic works of art by Spanish artists such as Mariano Benlliure and Ramón Álvarez.

There was so much to digest after this conversation… I learned about Zamora - a new (but actually really old) option for my desire to experience Holy Week. But wondered, where was Zamora? Was it even enjoyable if it was so solemn and reflective? The more I heard about it, the more intrigued I got.

And then I swear - with God as my witness - I heard my higher self say,

“You’re going to go to Zamora for Holy Week someday.”

BUCKET LIST UPDATE: SEMANA SANTA IN ZAMORA

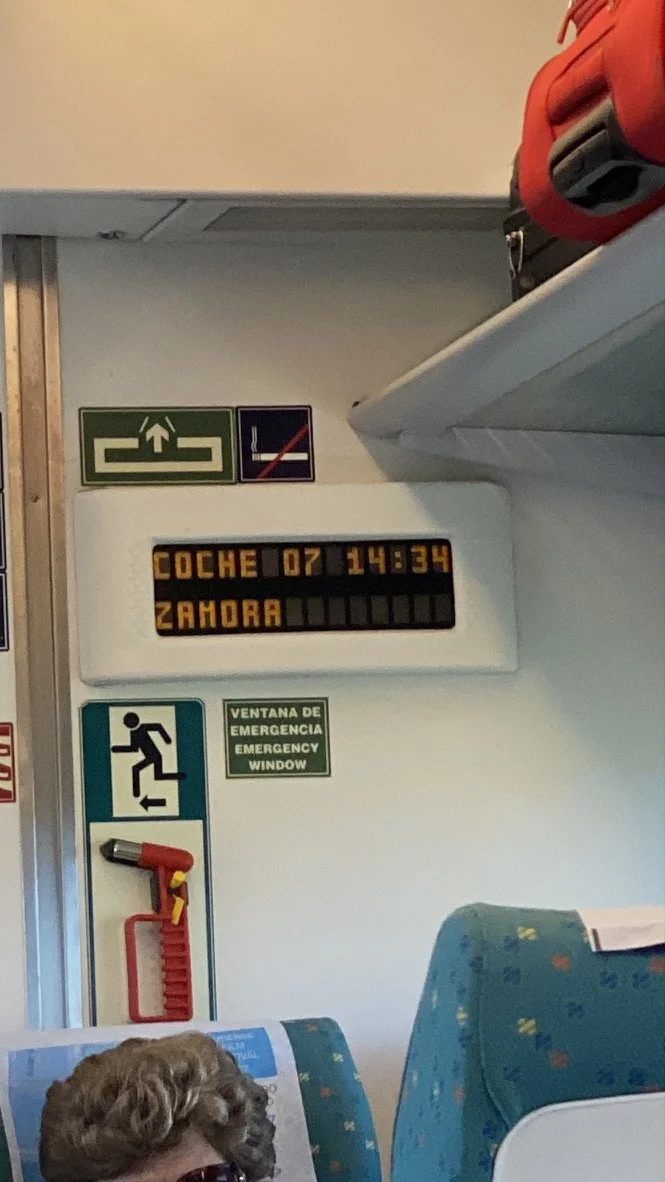

My conversation with Isabel happened about five years ago. And while I didn’t forget about Zamora, I didn’t have immediate plans to visit… until this past fall when I was on a train from Madrid to Montforte de Lemos to start a leg of the Camino de Santiago. Our train stopped briefly in (wait for it) Zamora!

I quickly Whatsapp’d Isabel, telling her where I was. I thought about what she told me about Zamora, including Semana Santa.

WAIT, DOES THAT SAY ZAMORA?

Passing through Zamora, I heard that voice again. This time it told me:

“You’ll be back in Zamora in the spring for Semana Santa.”

AND JUST LIKE THAT… I WAS IN ZAMORA FOR SEMANA SANTA

Thanks to the Tourist Office of Spain in Chicago and the Castilla-León Tourist Board, and the City Hall of Zamora, I found myself getting off at that Zamora stop this April… on an assignment to cover Zamora and experience Semana Santa.

Prior to my trip, I’d done a little research on Semana Santa in general and then specifically in Zamora. After all, I was the one with the stuck notion that Seville was the one place on the planet to experience Semana Santa. (Slight exaggeration, but not too far off.)

For my research, I had a team of experts on the case:

My friend Isabel, who sent me daily updates on Zamora

A priest from a nearby parish who was born in Spain

My friend Rocio, who comes from Andalucia & therefore knows a bit about Semana Santa in Seville

My old pal Google filled in the blanks but really has nothing on the above sources.

Based on all of the above, I learned the following:

Semana Santa takes place over 10 DAYS! Now, to experience it, you don’t need to come for 10 days… but it’s interesting to note there’s a pretty big window of opportunity to visit Zamora and catch a procession or two. Semana Santa starts the Thursday before Palm Sunday, continues through Holy Week, and ends on Easter Sunday.

During this time, the entire city is consumed with Semana Santa - there are banners throughout the city, store windows have Semana Santa displays, and people stop their regular routines to mark this occasion. People are generally off work during most or all of Semana Santa.

You might be wondering…

Is everyone in Zamora super religious and going to church at all hours? (NO!)

Do I have to be Catholic and very religious to experience this week? (NO!)

SEMANA SANTA… A RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL EVENT

While Semana Santa is about the Passion of Jesus Christ - telling the story of the last days of life, the crucifixion, and the resurrection of Jesus - many take part in the week for non-religious reasons. In Zamora, the week is not only an important religious event but an important social one as well. The entire city prepares and participates in this event - banners are found on every corner, store windows have Semana Santa figurines and references, and most importantly… the people stop their regular lives to observe this annual tradition.

While many do participate in Semana Santa for religious reasons, many use this week as a time to go inward and reflect on one’s life. It’s also a time to stop daily life and gather with family and friends - return to one’s roots and think about the important things in life. And finally, in Zamora, Semana Santa is a time in which the city can share its traditions and treasures with the world. This is the biggest week of the year in Zamora, and just as soon as one year’s celebration ends, they start planning for the next year. Months and months of hard work go into the creation of this one week - it’s everything to the people, regardless if they consider it a religious event/experience or not.

Zamora’s Holy Week differs from others throughout Spain because it’s much more solemn and reflective. The pasos (floats) are simpler and less elaborate than those found in Southern Spain. And while it’s true that there is a marked difference specifically between Zamora’s and other Holy Weeks around Spain, this is true for each Semana Santa - for the celebration not only tells the story of the Passion of Jesus Christ, it also tells the story of the people. Zamora’s processions are more solemn because their people have had to work hard over the years - working the land and dealing with the colder, more harsh conditions of northwestern Spain. The processions reflect the people and their struggles.

MY SEMANA SANTA EXPERIENCE

I arrived in Zamora on Wednesday of Holy Week… a great day to arrive, as I was able to witness two processions that night - “Ofrenda de Silencio y Juramento” or “Oath of Silence” and the Capas Pardas (brown capes).

Isabel and I were lucky to have VIP access to the first procession, the Oath of Silence, in the plaza of the Cathedral of Zamora. We arrived early and headed inside the Cathedral, where cameras were flashing and reporters were getting shots of the dignitaries and VIPs there for the procession. I also saw the penitentes (penitents, or those participating in that night’s procession) getting ready. They were adjusting their long white and red robes and preparing to don the traditional hoods covering their faces. This was a great time for me to ask Isabel about the hoods… for I knew many thought they looked like the Ku Klux Klan.

The hoods are called “capirotes” and cover one’s face in an act of penance… allowing the penitent to remain anonymous and reflect inward. Further, the tip points to the sky to indicate the conversation between the penitent and God.

Penitents outside the Cathedral of Zamora, prior to the “Oath of Silence.”

With this knowledge in my back pocket, we headed outside, where we’d watch the procession for the next hour and a half. The procession began while it was still light, with hundreds of penitents coming to the plaza, and ended in darkness, with penitents lighting candles. Ultimately, I saw an example of the famous pasos (floats with religious figurines) being carried to the Cathedral. It was a silent, reflective, and deeply moving procession.

The Oath of Silence ended just as solemnly as it began, with a paso of Christ on the Cross being carried in by penitents.

After the procession, it was off to dinner. The streets were FULL of people - all ages, from babies to the very old - headed to get spots for the night’s next procession, the Capas Pardas (brown hoods). While on the way to dinner (which, yes, would be at 10:30 at night- this is Spain, remember), we saw a man preparing to partake in that night’s procession.

This made me wonder… How are people selected to participate in the processions? Who were these people?

One of the penitentes who was making his way to that night’s procession, holding up the traditional “Capa Parda” (brown cape).

BEHIND THE SCENES… WHO PARTICIPATES IN

SEMANA SANTA?

Per Isabel, penitents are selected to participate in the processions, with each procession featuring penitents from different cofradías or fraternities - sometimes exclusively men, other times mixes of men, women, and even children. In addition, area choirs and musicians provide the typical Semana Santa music and participate in the processions.

Grown adults often return to Zamora to participate in one or more of Semana Santa’s processions because participating is considered an honor and a significant life event. One must first be accepted into one of the cofradías - some have direct entry, while others have a long waiting list, where names are added at birth. For these cofradias, the wait can be years- as one Spaniard told me, “Someone has to die for me to move up on the list.”

Isabel with friends who were part of the Capas Pardas.

ALL AGES GATHERED

While the procession lasted until early Thursday morning, all ages were gathered to watch.

Fun fact: A typical snack eaten by many who watch the processions is the shelled pepita or “pipas.”

Additional fun fact: Zamorans like to keep their streets clean - they invented a special bag to accompany the snack; shells go in the “pipelera.”

The Capas Pardas procession began at midnight and ended a couple of hours later, with a choir singing in Latin and a paso (float) of Jesus being brought into a church.

At 2:30 a.m., it was time to get to bed, so I’d be ready for the next day’s “Cofradia Virgen de Esperanza” in the main square (Plaza Mayor) at 10:30 a.m. Friday.

The Cofradia Virgen de Esperanza had an entirely different look and feel than the previous night’s Oath of Silence and Capas Pardas for a number of reasons. First, the participants were women, called “Las Hermanas” or sisters - of all ages - dressed in black dresses and tall black hair combs holding veils. Intermixed with the women were men wearing capirotes, and a band followed the procession, introducing the paso carrying the Virgen de Esperanza. It felt much more majestic than the solemnity and silence of the night before.

La Virgen de Esperanza.

After this procession, I took some time to take in the sights of the city, like the Plaza de Viriato, river walk along the Duero River, and grab a drink at the famous Los Herreros Street where there were plenty of tapas, drinks, and food. Los Herreros Street definitely felt like the place to be - a meeting spot to celebrate the festivities.

Plaza de Viriato

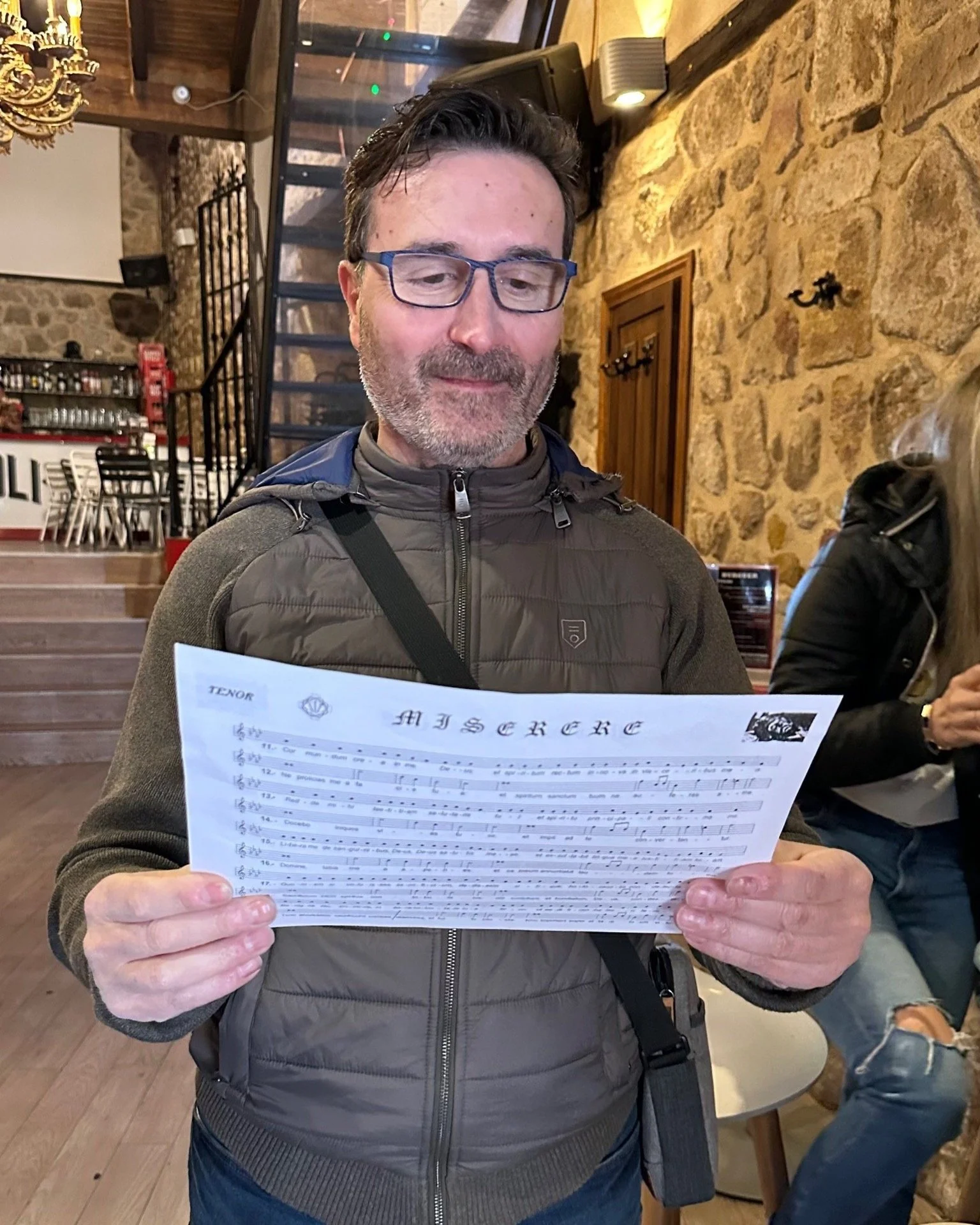

Isabel and I ran into a friend of hers named Angel, who’d been practicing for that night’s procession. He gave us a preview of the beautiful Latin hymn he and fellow choir members would be singing during the late-night procession (it would start at 11:00 p.m.) called the PENITENTE HERMANDAD DE JESÚS YACENTE. He explained that the brotherhood (consisting of 1300 penitents) in that night’s processions would be wearing white robes and hoods. After winding through the streets of Zamora, the brothers would end up at La Iglesia de Santa María la Nueva (the Church of Saint Maria) where the choir would sing the CANTO DEL MISERERE. I’d later be able to see and hear this moving procession.

Angel giving a preview of Canto del Miserere.

After a bit more walking around Zamora, I headed back to my hotel for a siesta… which I would need as that night’s processions started at 11:00 p.m. and ended after 7:00 a.m. Friday morning. Semana Santa will keep you going, no doubt about it. But note that you don’t have to attend every procession (there was a 4:30 p.m. procession that day, for example, that I didn’t attend).

At 11:00 p.m., we were back at it to watch the procession of the Brotherhood of JESÚS YACENTE. This consisted of 1300 men in white robes, hoods, and a purple belt. The brothers carried candles, giving the atmosphere an even more reflective feel. Several walked barefoot; all were walking to the final point where the choir would sing the Canto del Miserere, somewhere around 1:30 a.m. While this felt like a great time to call it a night, that was not to be the case, for another procession was right around the corner at 5:00 a.m.

Penitents from the Brotherhood of JESÚS YACENTE during the 11:00 p.m. procesion.

To kill time, the crowds headed towards Plaza Mayor, where bars and cafes were open with plenty of food and drinks for all. Staying up all night is part of the experience, and while it was pretty grueling at times… the atmosphere was of anticipation and excitement. People were laughing, drinking, eating… enjoying the night. Isabel and I grabbed a Coke Zero in a cafe inside Plaza Mayor and started talking to a documentary producer and director, Xabier Xalabardé. He’s been working on a documentary about Zamora’s Semana Santa for the past six years. (Some of his stunning pics can be seen @xabierxalabarde on Instagram.)

5:00 a.m. came around, and Xabier led Isabel and me to the press area inside the Church of San Juan de Puerta, which was also nearby in Plaza Mayor. Inside, we saw the penitents and band preparing for this procession. It was a behind-the-scenes experience where I saw the participants hugging, laughing, and talking with each other. The band was warming up. There was a nervous but excited spirit of anticipation in the air - all getting ready for this early morning Good Friday procession, which would go for hours and end up at the site of Zamora’s Holy Week Museum. Procession viewers hang in there until the end of the procession and then enjoy the traditional “Sopa de Ajo” or garlic stew, served after Friday’s early morning processions.

Preparations and photos before Friday’s early morning procession.

All ages participate in the processions, and some penitents repeat their participation for years. The pictures shown show the spirit of the occasion… truly a brotherhood and sisterhood, proud to be part of the traditions of Semana Santa.

Two more days of processions would follow, each equally as moving, and the culmination being the Procession of the Resurrection on Easter Sunday. You really have to experience Semana Santa in person to feel the history, tradition, emotion, and spirit of the people that come out in every procession.

From the brothers and sisters who take part in the processions to the crowds that gather to watch, one can sense the pride the people have in their Semana Santa and in Zamora. Their devotion to this tradition - coming back year after to pause from daily life to literally spend hours in silence - reminds us all of the need to stop and reflect.

It’s only when we pause and go inward that we start to make sense of what’s happening outside of ourselves and go about the business of living our lives to the fullest.

A photo of me on a balcony watching the procession of La Virgen de Esperanza fade into the distance.

Share Post